Her siblings were at least:

- William born 1757

- Alexander born 1759

- Bethick born 1761

- Jean born 1767

- Francis born 1769

- Henrita born 1774

|

| The old Golsary homestead. |

- When she was nineteen, on 1 April 1784, Katherine married John Sinclair.

- In 1787 Katherine's first daughter Marion was born.

- John Sinclair died leaving Katherine a widow and Marion a fatherless child.

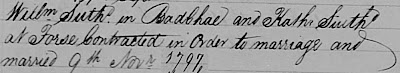

- In 1797 Katherine Sutherland married William Sutherland of Badbhae whose first wife Christian Finlayson had also died. Katherine was thirty-two years old and William about fifty-one.

The following year, 1798, the first child of this marriage was born. This baby girl was named Christian Sutherland, probably named after her father's first wife. The birth record of Christian has not been located but many other records of her life have been found. She was later known as Christina in keeping with changes in naming customs in Scotland. She is my ancestor. Christian was raised in Badbea. At home there would have been at least some of her half-brothers from her father's first marriage and Marion her half sister from her mother's first marriage.

Malcom was probably the next child born about 1800 to Katherine. His birth record has not been located. There are passed down stories of this Malcom drowning in curious circumstances - more later.

John was born in 1802.

Esther was born in 1803.

Margaret followed in about 1805. Her birth record has not been located but there are other later records of her life.

Alexander Robertson was born in 1807. There are many later records and stories of the life of Alexander (aka Sandy). Most records refer to him as Alexander Robert. He emigrated to New Zealand in 1839 and is the chief subject of the book Sutherlands of Ngaipu by Alex Sutherland his grandson.

About 1810 tragedy hit this family. William and Katherine Sutherland both died. Did they die about the same time as each other from a sickness such as TB? Or did they have an accident? There is no further information available. The old family historian John Sutherland says, "When the family of this marriage were quite young, both parents died, leaving them not very well off." William was about sixty-four and Katherine forty-nine at the time of their deaths. What a calamity. Christina at 12 years old, Malcom 10, John 8, Esther 7, Margaret 5, and Alexander 3 were left orphaned.

Source: Sutherlands of Ngaipu, Alex Sutherland, AH & AW Reed, Wellington 1947, pg 14.

|

| The old Golsary homestead. Did the orphaned children come here for help? |

|

| The Golsary Sycamore tree with the grass covered broch behind. |

Source: Comraich, John O Groat Journal, June 10, 1977.

|

| The wall of an early house at Badbea |