The Great Frost of 1740

On June 29th 1740 following the Latheron elders discussions and concerns about the dismal seasons, the session clerk recorded the following:

“The Session considering the melancholy and dismal circumstances of the country in general and of this parish in particular being very causable that our sins and transgressions against the laws of God and the laws of the land are the procuring cause of the threatening dispensations of his provenance with respect to the penury and want that the bulk of people labour under and also with respect to the dismal season wherewith the fruits of the earth are threatened with by reason of the high and severe winds that now fill the heavens”.

“Therefore they agree that Thursday the tenth day of July next be set apart as a day of fasting [going without food for a time] with prayer and supplications. That God would be merciful to our unrighteousness avert his threatening compassion at our case and speedily relieve the wants of the poor of the land and finally that he would turn the hearts of all mankind to Himself and appoints that this be intimated next Lord’s Day”.

Distributions to the poor.

As well as fasting with prayer and supplications the elders got together what little money they had to distribute to the poor.

“The minister informs that some of the elders did meet at Landhallow according to appointment and distributed about thirty six pounds Scots among the poor”.

“The session considering that there is no poor roll they appoint that a full roll be made up of all the poor in the parish and that the said roll be inserted in the session minutes in all time coming”.

On November 9th 1740 another day of fasting was agreed on by the elders.

“The Session appoints that a parochial fast be held the eighteenth day of this instance for the melancholy sake of the harvest”.

On July 21st 1741 a list of the poor and the distributions that were made were recorded.

There were sixty five names on roll. £38 7d 8p was distributed. Most people on the poor list got under one pound with many receiving 6 or 8 shillings. I wonder how far that went to allay their hunger and feed the children.

Why are the elders so concerned?

The Little Ice Age

The period and geographical spread of the ‘Little Ice Age’ seem to be contested by scholars. I have no expertise in this topic but as far as I can determine the period 1300-1850 had temperatures far too cold for comfort.

|

| October snow at Achavanich |

What does seem to be agreed upon is that the “Great Frost” of 1740 was one of the coldest winters of the eighteenth century and impacted many countries all over Europe. The years 1739 –1741 were a period of general crisis caused by harvest failures, high prices for staple foods, and excess mortality.

The 1738 - 41 Harvest Crisis in Scotland

The great Irish frosts in 1739 and 1741 were not exactly the same as conditions in Scotland but both countries suffered greatly from the cold. During the Great Frost of 1740 Scottish records show that the country remained frozen until the end of May that year.

The Great Frost is believed to have been made worse by the volcanic eruption of Mount Tarumae in Japan in 1739 which sent thousands of tons of dust into the upper atmosphere thereby restricting incoming solar radiation for several months and resulting in extreme cold for two years with bitter winds, freezing temperatures and droughts.

|

| Mount Tarumae erupting in 1909 |

.With reference to Scotland Rev Charles Gordon stated:

“…in the famine of 1740, a late winter was accompanied with a terrible frost, which binding loch and river, also restrained the husbandman.The frost continued to the end of April, no seed being sown till May. Rough and sunless weather prevailed during summer, resulting in a stunted and almost useless crop. For rent there was no provision, while the fodder was barely sufficient to sustain the cattle. On account of this terrible visitation the progenitors of Robert Burns, who had held respectable rank as Kincardineshire yeomen were reduced to poverty, and the poet’s father was compelled to migrate southward in quest of work. Other northern farmers shared in the common ruin. Many landlords too were impoverished...”

https://electricscotland.com/history/sociallife/chapter6.htm

1739.—SEVERE FROST.—According to an old MS. Note, the frost which “set in about the middle of Dec. 1738, continued for 107 days, “ for it did not give way until March 29th this year.” Dunfermline was “distressed for want of pure water.

1740.—GREAT SNOW STORMS.—An old MS. informs us that during “the whole of the month of January in 1740, Dunfermline was visited by terrible storms of snow, and that where it was drifted it was at least 24 feet deep.”

https://www.electricscotland.com/history/dunfermline/chap8part5.htm

What the elders did

So the kirk elders did what they could, which was probably much the same as would be done by ‘church going’ people today under similar circumstances. They organised prayer and fasting then they made a list of the poor in the parish and distributed what funds they had.

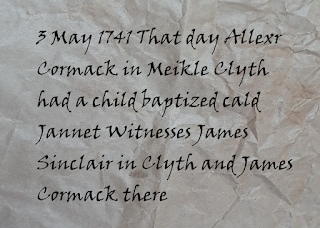

www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk Latheron kirk

session, Minutes (1734-1776, with gaps) (1754-1783, with gaps), CH2/530/1 pgs 79

– 83

P R Rossner, The Scottish Historical Review Volume XC, 1: No. 229: April 2011, 27-63

.jpg)